July 2017: With the car freshly rebuilt, we headed to Lincolnshire and the notorious Cadwell Park circuit. Billed as a mini-Nürburgring of our very own, this is a narrow ribbon of tarmac that winds its sinuous way through huge elevation changes, surprise cambers and challenging complexes. It’s thoroughly enjoyable when it starts to flow, but needs approaching with care and respect. Not the simplest of places to prove out the car after its shunt!

As usual, we did a track day two weeks before to check the car over and learn the circuit. I was relieved – and mightily impressed – to find the car seemed no worse off for its ordeal. Is there no limit to the punishment a leggy 90s German saloon can take?!

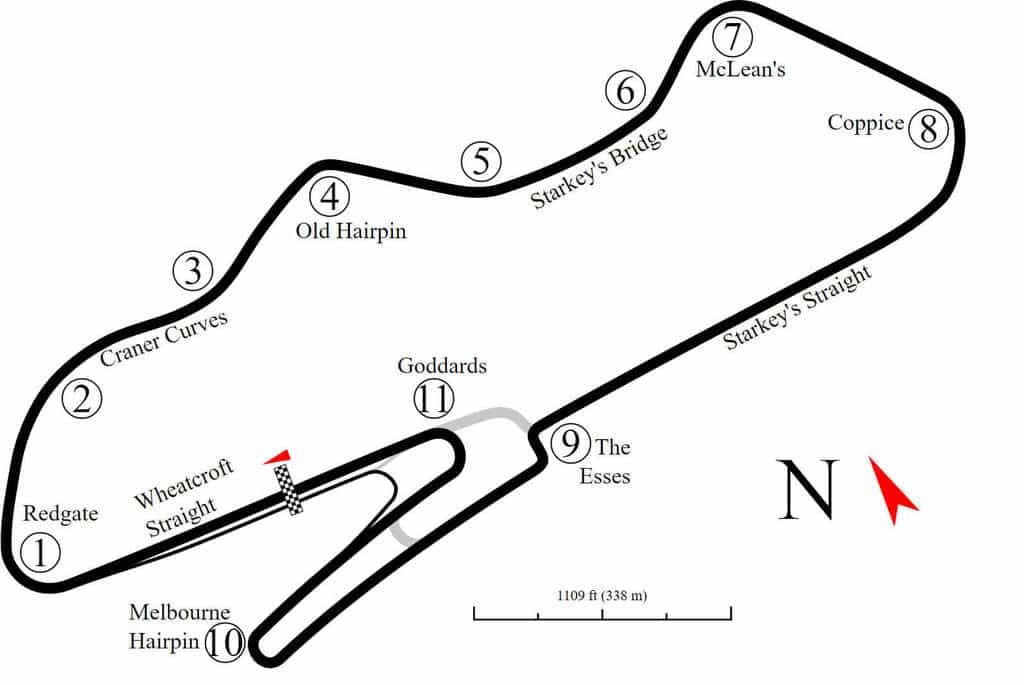

Race day came swiftly after, and served up the most dramatic qualifying session we’d had so far. All was going well for the first two laps of my run, until suddenly a loud, boomy vibration and occasional scraping noise could be heard in right-handers. It wasn’t until I heard a loud scrape climbing The Mountain that I realised the back half of the exhaust had come free, and was so loose it was moving around to foul the body and even the track surface! I managed to finish one more timed lap before I was shown the black-and-orange flag to bring me into the pits. The marshals made it clear that unless we could fashion a means of securing it, we couldn’t go back out, and James wouldn’t be able to qualify to enter the race.

With the last few precious minutes of the session ticking away, the true spirit of club motorsport came through. Our chief competition, Adam Chafer in his Peugeot 206 with his family team ISLA Motorsport, jumped into action to help us get the pipe secured enough to get James out and do some very gentle laps to qualify for the race. We’d have been deep in it without our rivals helping us, quite possibly not making the start – they came to our rescue because they wanted the chance to race against us, which is what it’s all about. Hats off to them.

It turns out that it’s still possible to set the class pole position lap while your exhaust is flailing around in a mad bid for freedom..! That was more than enough excitement for one day, yet when the start rolled round I found myself sitting 18th overall on an incredibly cramped grid of 27 cars on a circuit that felt big enough for maybe six. I hadn’t felt nerves as bad since my very first race, but I got away cleanly and managed to survive the first few laps and give some good battle to the cars around me.

After around ten minutes there followed a long safety car period to extract a BMW from the barriers after Charlies corner, after which I was able to do some really great racing. The car felt good and the circuit was making sense, and I had cars around me at competitive pace – it was a brilliant feeling being able to race the car hard for lap after lap. I came into the pits from the class lead with twenty minutes left on the clock.

We were hobbled once again by a success penalty adding 25 seconds to our one-minute pitstop, and rejoined several places down. James was left with a relatively quiet stint to bring the car home, mostly focusing on traffic management as faster cars from the classes above came through, trying to lose minimal time in the process and pull back to Adam Chafer’s now class-leading 206. Sadly it wasn’t enough, and we crossed the line 2nd in class and 19th overall, 28 seconds behind Adam – a scant three seconds more than the success penalty had cost us, robbing us of the opportunity for a close fight to the flag. Here’s the race video:

As much as it felt a shame to “only” finish second, I came away feeling quite satisfied. We’d managed to get the car to the next race after suffering a crash on the road, and it still had shown class-leading pace in qualifying and in the race. Bearing in mind that I’d started the season with the idea that finishing races would be a huge personal success, we were still flying high!

Sam