Where even to begin, writing about an event like the 2CV 24hr race? You may already know how I ended up here, though if not, take a look at the background – which also has some more information on the car and some testing footage. The story now resumes on Thursday 16th August, arriving at the circuit to see the car already in its garage, buried in the midst of a paddock that looked entirely more serious than any other club race I’d been to! Everyone seems to have motorhomes, caravans, huge awnings and gazebos, entire kitchens built opposite the garages and almost all the cars were already here. Our neighbours Jelly Snake Racing were already filling the atmosphere with the smell of scorched metal as they took the grinder to the rear of their car at 10pm. The mood was well and truly set.

After a couple of hours getting the garage sorted out and the car mostly ready for the test day that would start on Friday morning, we took advantage of the darkness to set up the headlamp aim in preparation for night qualifying. I got my first taste of the surreal feelings a 24hr race can give you.. Standing in a pitch-black pitlane, a place typically filled with noise and light and people, and drinking in the absolute emptiness of it all.. four hours after everyone would normally have packed up and gone home. Quite a special feeling, and it brought real excitement for the meeting to come. And a real awareness of just how bloody dark it was going to be out there!

Friday was a normal test day, as typically precedes any club racing meeting.. Though despite having been to nine races of my own in the past, I’d never actually run on a test day before! Very different to a track day, this runs essentially like a series of qualifying sessions, with driving held to motorsport standards and groups of comparable cars let out for 30-minute sessions over the day. With no briefing to sit through, live timing permitted and the ability to run side by side with other cars, it was a useful initiation for me, having never driven the 2CV in close combat before.

There was still much work to be done, though – we had three engines with us, one of which we were reasonably happy with, and two that needed setup work on the day. So as well as adapting to the car and circuit, and seeing if our times were in the right ballpark, it was also a day of carb jetting, brake bedding and fault finding, with a customary lunchtime engine change. By 5pm we’d finished our last session and had a couple of hours to grab some food and make final adjustments before day qualifying started at 7pm.

This is when the event started to feel real. I’d already wandered up and down the pitlane and taken stock of the competition – 24 UK 2CVs to the same specification as our car, plus six 1275cc Minis and three Belgian Dyane/2CV hybrid cars running alongside us as guests. The latter are a world away from the near-standard 602cc UK cars, and run 850cc BMW bike engines with full aero packages and sequential gearboxes. They ran Snetterton 200 in around 1:36, with the fastest UK club car lap over the weekend being a 1:51! The Minis were also considerably faster over a lap, so like all good endurance racing, the multi-class element was present and correct. But now, testing was finished and all these cars were lined up the pitlane for the first competitive session of the weekend.. after months of planning and anticipation, it was all about to start.

We elected to run our drivers in the same order we planned for the race, as good practice both for us and for the pit crews adjusting our belts and strapping us in – so Graeme Smith would start, car owner Christine Savage next with me to follow before handing over to Christine’s brother Neil. We’d each run five flying laps, but sending Neil out last meant we could leave him out to the flag after we’d all done our laps – advantageous, since he’s the quickest driver and you can only achieve a really good lap in a 2CV if you have an aero tow from another car, which can take a while to find.

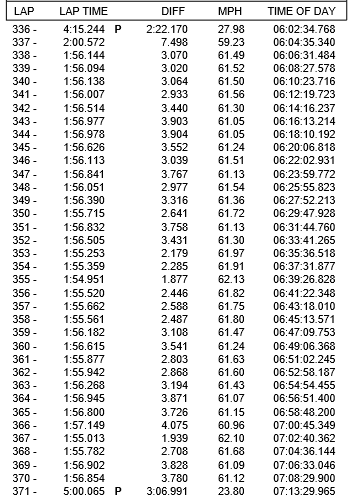

Graeme and Christine both ran good pace for their sessions, and I went out keen to put in a strong performance – but found myself marooned, with no other cars anywhere near me! With contending for the car’s fastest lap out of the question, I could concentrate on attacking the circuit as cleanly and consistently as possible. The lap timer made me smile each time I crossed the line, clocking 1:56.32, 1:56.27, 1:56.43, 1:56.71 and finally making a small mistake for a 1:57.13. The rhythm was very reassuring for putting in a smooth race stint the next day, and I got out quite happy.. Until Neil immediately got under my lap times in clean air, that is! Turning in 18 laps with an astonishing average pace of a low 55, he finally found the perfect tow – behind the slower of the Minis – and turned in a 1:53.92 with 15 minutes of the session remaining. The fastest the car had run for the whole of 2018, it was still only enough to put us 11th in class and 20th overall on the grid of 33 cars. Clearly, the pace of the frontrunning cars – UK pole being a 1:51.21 – was on another plane and we’d need to push hard to stay competitive.

I was pretty comfortable driving the car in daylight, but night qualifying was next and I had never driven a circuit in the dark before. To give me maximum exposure, we swapped the driver order to put me last after Neil. Everyone else would only do the minimum required three laps to let me run as long as possible – at least, that was the plan until Neil picked up a great tow and carried it for two extra laps to clock a 1:54.95, putting us a brilliant 6th in class for night quali! Watching this was plenty exciting, but it left me more than enough time standing on the pitwall in my helmet and suit, stewing about how dark it was out there and how much was riding on me not screwing up and bending the car.. Apparently this is the face you pull in such situations.

Before I knew it, Neil was in, I’d been strapped in and waved out of the box. You don’t really think, you just put your foot down and drive up the pit lane, with the pit exit into first corner being all flat out up to fourth gear in a 2CV. I did this on routine, figuring the circuit should be where I left it and trying to ignore the nerves – but the moment I turned in and saw the apex kerbs lit up in the headlamps, I felt absolutely euphoric. The car was just doing what it always did, but your visual cues are so limited, everything appears ahead of you just when you need it.. Sometimes slightly after! The darkness forces you to focus on the next job and nothing else. There’s the bollard on the second apex.. there’s the white line on the outside, just picked out at the edge of the headlamps, aim for that on exit.. I can see the brake markers up ahead, I’m pulling roughly the correct revs in 4th.. hit the anchors, drop two gears and turn into Montreal. Look right over through the corner, can’t see the inside kerb yet, just blackness.. it should be there, commit and keep turning.. there it is! Power over it, around Turn 3 and onto the straight.. this is awesome!

I managed to clock consistent laptimes that were on the same pace as the daylight run, so I came in happy at the end of the session at 10pm. We all felt the car was pretty much where it needed to be mechanically, so after a Strategy Group Meeting – drivers huddled around the car to debrief – and a swift beer, it was off to bed to sleep for as long as possible.

Even now, having done it all, it seems surreal looking at the photo of the car sitting there waiting to race for a full day and night..

Race morning dawned late for me, aiming to get to the circuit just in time for the briefing at noon, and to do final prep before the 20-minute warmup session at 13:20. That would be the only running available before the race start at 5pm, so we elected to trial a couple of final carb jet tweaks. I drove, feeling the mounting anticipation, but the car felt good so we settled into final tidying and prep.

Just before the pitlane opened at 16:30, all the cars and teams were brought out of their garages for photographs and an open pit walk for the spectators and supporters. Quite a special moment – yes, they’re only simple little cars and nobody was going to be setting a circuit record that day, but these crews had spent a year preparing to try and do over seven hundred laps of Snetterton, stopping for nothing but fuel and driver changes. An enormous undertaking.

With the fuel tank brimmed right to the top of the filler, Graeme cruised around to the grid before the field were waved away for their green flag lap and the rolling start. Right on cue at 17:00, the lead Belgian cars powered down the pit straight for the first time to start the 2CV 24hr race.

Graeme got on it straight away and kept with a reasonably-sized pack of cars, after a bit of battling for position settling into some good tows and clocking consistently quick laps. Aside from a brief safety car period at Lap 15, the race got off to a smooth start with little incident. We settled into tracking Graeme’s progress from the pit wall, in lap times and gaps to the cars around him, before showing him the FUEL ? board at 7pm, after two hours racing. That tells the driver that the refuelling crew is ready for them, and it’s now their discretion when to come in – as only they know how much fuel they have on board, how the car feels and whether they think it’s worth staying out to take advantage of good track position.

But almost immediately, a problem – Graeme lost two seconds’ pace the lap we showed him the board, and then four seconds’ more the next lap, where he passed us waving his right arm to indicate he was coming into the pits. He arrived in the pit box reporting the engine losing power and unwilling to rev out, and the moment we opened the bonnet the reason became obvious – almost all the oil was spread across the front subframe and crankcase, rather than in the engine. “No decision – we’ve gotta change it”.

Of all the starts we envisaged, this was the very worst! But no time to worry or resent the fact, we are racing, so we pushed the car back into the garage and began methodically stripping the front end off and getting the condemned engine removed. Foresight of many 24hr races had led us to lay out kits of the tools needed on both sides of the garage, so everything we needed was largely to hand, but not remotely helped by being coated in oil! Thirteen minutes after being pushed into the garage, the car fired with its second engine installed. We wheeled it out, refuelled it, and strapped Christine in for her one and only stint. Handshakes all round as she drove up the pit lane, and much further relief when she came past with a thumbs-up out of the window after her first lap!

An engine change was something we expected at some point in the race, it’s not uncommon, but to need one straight away was worrying. At least the car seemed OK, with Christine putting in 62 consistent laps into nightfall before diving into the pits the moment we showed the FUEL ? board. I was on the pit wall, suited up and helmet on ready to get in the car, and partly grateful at not having to wait for lap after lap to get going, but it seemed a short stint at only 2hr08. The moment Christine pulled up, she reported the engine running much too lean – the lambda gauge telling her that the fuel/air mixture was too little fuel and too much air, giving us a risk of overheating and damaging the engine. While fuel was poured into the tank at one end, new carb jets were screwed in at the front, before I could leap into the car and get strapped in. After a few moments’ pause, I was waved up the pitlane to join my first endurance race, my first night race, my first 24hr, my first racing laps in this car…

And man, was it incredible. I was determined to get it nailed right from the off, and put in a 1:56.88 on my first flying lap – with a different engine and now in full dark, that was only half a second off my day qualifying pace, and put a huge smile in my helmet. Adapting to the race traffic at night was easier than I expected, with the noise and the changing light making it quite obvious where cars were around me, but what took more acclimatisation was just how close you can race these things. Being side by side, close enough to tweak a rival’s door mirror, for an entire corner is not at all unusual. Nor is going three-wide into a corner which only has one sensible line! After all the preparation and apprehension, and the early dramas with the engine, getting out there and really racing this car hard felt absolutely amazing. How does it really look? A bit like this.

A full highlights video will come eventually, but this – the first four minutes of the first clip I happened to pull off my GoPro – hopefully gives you some idea. It is unspeakably brilliant. I could wax lyrical for hours on every aspect of night racing, but I’d bore you all in the end, so suffice to say that I punched in 78 laps over 2hr38min, and only came in the pits – still with a healthy amount of fuel on board – because the team signalled me in, thinking I was about to run out! I could cheerfully have run right to the 3hr driving time limit, so fantastic a time was I having.

I jumped out of the car thinking it was still running a little lean, so while Neil was being strapped in, I grabbed the carb jet box and made a change I’d decided on a few laps before – fresh out of the car and still in full race kit, I was surprised with myself getting it done in good time before sending Neil off into the night at thirteen minutes past midnight. The camaraderie of 2CV racing shone through a little when a driver from another team congratulated me on some “top spannering” getting the jetting change done in the dark without a torch to hand – a little boost on top of the massive high I was already on from one of the drives of my life!

Ideally, you’d be asleep or at least resting the moment you get out of the car, such is the need to conserve energy. But funnily enough, when you’ve just been dicing wheel-to-wheel with the leader of the race for an hour straight, sleep isn’t first on your mind, midnight or no! So I did a stint on the pit wall seeing how Neil was getting on – bloody quickly, naturally, but happily for me only around three quarters of a second faster than I’d been going in clean air. A good showing for a 2CV novice, and more than close enough for me to pretend to him that it was down to the improved jetting I gave him..! I then popped up to Race Control to say hello, and finally up to the commentary box, where I found 750 Motor Club regular Josh Barrett, who was kind enough to give me a microphone. I’m quite sure I talked absolute nonsense for the quarter-hour he had me, but I appreciated the conversation and the opportunity to share my very fresh thoughts on how utterly brilliant this whole endurance racing malarkey is.

Finally, my head went down in the tent at around 1am, with Neil barely a third of the way into his stint. He would go on to set the sixth fastest lap of the race, a 1:53.07 – yes, nine tenths faster than we qualified, and yes in the black of night. We’d climbed back to 7th in class despite our engine change. Maybe we could get a result out of this?

I woke a little earlier than planned at 3am. A text from Christine. “Graeme is in the car.. has been since 2:20 but had to be towed back in for a disconnected gear linkage. We’re in 15th”. The heart sinks – all the further when a moment later, the phone rings with Neil: “We’re in the garage, gearbox change – better get ready, Graeme’s getting near his driving time limit”.

A gearbox?! That’s half an hour, and we’re already down in 15th. But the effort put in by the crew, who had already been up for at least 18 hours at this point, was nothing short of stellar and Graeme was back out on the circuit by half three and got 25 more laps done to round out his stint. At half past four, I was out on the circuit and ready to drive on into the dawn.

I’d been a bit worried about this stint, aware I’d be far more tired and prone to errors, but in fact the muscle memory from the earlier night driving was present and correct and I was able to get onto a consistent pace fairly quickly. I was just starting to appreciate the brightening eastern sky, and the ability to see things that were just outside the range of my headlamps, when after 26 laps I saw something far less welcome. Smoke. Oil smoke on the left side, just as I was driving past the pits.. Argh! I gestured wildly to let the team know I’d be coming in, and started short-shifting to nurse the car back. A little dejected by yet another failure, we pushed back into the garage and the crew set about changing to the third engine carefully, making sure everything was exactly as it should be. A fairly shattering process for all involved, by this stage of the race.

At ten to six, I was pushed out into the dawn light with engine number three turning and burning, and powered up the pit lane to finish my stint. The perils of mid-stint engine swaps became apparent straight away when I struggled to find second gear into Montreal on the outlap – whoops – this clutch bites far lower than the old one, and once I get lost in the intricate 2CV gear selection, it’s hard to find the reference plane again! But with that embarrassing episode out of the way, I settled into the most satisfying drive of the race. I had traffic around me, but was faster than every other UK 2CV I came across, carving past slower cars and tucking onto the back of quicker ones for a few laps’ tow before leapfrogging to the next one. It felt fantastic, and was also the most consistent drive I’ve ever done – of the 32 flying laps in that run, 24 of them were 1:56s. The slowest over that hour was a 1:57.1!

The IN board stopped my fun at ten past seven, 2hr40min after I’d first got in the car, but thanks to the engine change only 65 laps further along. 742 miles completed, ten hours’ racing left to go. After checking Neil had settled in OK, it was back to the tent to get some more rest before being due back out at around 11:30.

That didn’t turn out to plan.

The third engine had started to develop a death rattle just before 9am, towards the end of an awesomely fast stint with Neil doggedly dragging us back up the rankings. The team decided to pull it out to save it for the end of the race, to make sure we could finish, and sent Neil back out with the first engine in. It was no good, 18 hours’ cooling down hadn’t saved it, and after one lap it was back in the garage covered in oil again. That was it, no more quick swaps, we didn’t have another running engine..

There was nothing else for it but to try and produce one running engine out of numbers one and two. Stripping them on the garage floor, Neil and Jon found that both had wrecked their right-hand pistons, with excessive knocking damaging them so badly part that the ring lands were gone, letting the oil through.

So it was that the left-hand piston and barrel from one engine became the right-hand of the other! The joys of working with such a simple engine were not lost on me as I got kitted up while this Frankenstein’s monster of a power unit, rebuilt and sealed up on the garage floor, was bolted back into the car for me to go racing again. Try doing that with any other endurance racer…

And you know what, it felt pretty good. A bit tight.. that’s perhaps to be expected.. I had to nip into the pits again for a carb jet change, but only once, which is pretty good for saying this engine didn’t exist two hours prior! I was able to run only two seconds per lap slower than before, no longer able to keep pace with the fastest cars out there, but well in range of towing and dicing with much of the field. It led to a uniquely 2CV game of chess, with a car that was considerably faster than me in a straight line but that I could still just about hang onto over a lap – the battle was to make sure that I used all the other traffic to the absolute maximum, pulling myself along and nipping past slower cars as quickly as possible, to stay in touch. After losing contact and being stuck behind someone else for a few laps, getting back through and back where I needed to be was a fist-pump moment!

Apart from an electrical failure that cut all power, which fortunately happened in the penultimate corner so I was just able to coast to the pits without needing a towback – the points box was the culprit – all went fairly smoothly. I got out of the car for the last time at just gone 2pm, having notched up a total of 185 laps over 6hr10 of driving time and feeling very happy with my endurance racing debut. What’s more, I felt like that engine could actually go the distance. Off Graeme went to put in another hour, before we’d run Neil to the finish. With that final change made and Neil out to bring the car home, I wandered off for a shower, my driving work done for the day and my kit in the worst shape it had ever been, after 26 hours’ wear! Sleep deprivation might be starting to tell, too.. in drivers and crew!

Imagine my dismay to get back at 3:40 to find the car in the pit box, in a cloud of its own smoke. Can we not catch a break?! Engine number four, as I’ll call it since it certainly didn’t arrive with us like that, had brilliantly done three hours before finally expiring in a similar failure mode of huge oil blowby. We parked the car with an hour and a quarter to go, fitted the saved number three engine, and waited for the last few minutes.

A quirk of 24-hour racing is that in order to be classified, you must finish the race – which means the car needs to be on the circuit to take the chequered flag. In 2CVs (unlike Le Mans), you’re also classified if you’ve done 80% of the race winner’s distance, but you can imagine with 6hr40min unscheduled pitstop time this wasn’t the case for us – we had to get over the line. So it was that Neil lined up at the end of the pit lane at 16:57 to get out and do one final lap.

A party atmosphere was already in evidence, with the pit wall crammed with teams waiting to applaud the cars as they came through. The chequered flag came out at 5pm, twenty-four hours of racing complete, and the lead Belgian car came through to take it after 788 laps – 1,576 miles of Snetterton in a day and a night. The winning UK 2CV had racked up 708 laps. Team Stinky crossed the line with 491 laps to its name, making a godawful rattle, but taking the flag to complete the 2CV 24hr race!

Getting back to the pits, on the other hand…

The engine we’d saved had been pulled out of the car not a moment too soon, and expired halfway round Coram on the cooldown lap. Fortunately, the spirit of helping others get the job done is alive and well in 2CV racing, and we were pushed back to the pits and up to parc fermé by our neighbours Jelly Snake Racing. An adjacent team manager summed up the situation when the last car had rattled through: “Right. Let’s get the beer open.”

A disaster it may have been in competitive terms, certainly the worst race Team Stinky had ever known, but we’d got the car across the line and I had had the experience of a lifetime. I’ll never forget that first lap in the dark, and the thrill of night racing – yes, I know I mentioned it – is unbeatable. But more than that, 24-hour racing demands something totally different to sprints or even shorter enduros. While you are racing everyone out on the circuit, that’s not really the job. You’re trying to beat the event. Your job is to get as many laps done as quickly as you can, but you can only do it with smoothness, consistency, mechanical sympathy, and a brilliant team behind you to keep the car out there and pick up the mantle when you’re done. And that means everyone from the drivers, the mechanics, the cooks, the fire marshals, the fuel-fetchers, the poor souls on the pit wall with the stopwatch day and night.. It’s a team sport, and getting through it together is fantastic.

Yes, Emerald went the distance! As always.

Thank you, Team Stinky. Absurd the name might seem, but great the achievements are. Christine, Neil, Linda, Graeme, Kevin, Jon, Chris, Jesus, Karen, Sarah, and as always Mum & Emily – and all the rest of the paddock who kept us fed, advised, pushed home. Unforgettable. Same time next year?!

This and much of the other great work in here is credited to Joshua Barrett Photography

Sam